Thursday, August 9, 2012

Questers into the Unknown

I have been working again on Questers, this time translating it to Dungeon World. So far, this is my progress. Let me know what you think, and I will add it to the blog Treasury for future access. Credit where credit is due, it owes a lot to Vincent Baker (Apocalypse World), Sage LaTorra and Adam Koebel (Dungeon World) and Ryan Stoughton (E6 D&D). And while we are at it, here is an excellent map of Unknown Kadath.

Wednesday, August 1, 2012

Bonded to the World

In many ways, how players are rewarded at the table will define your game, and thus your game world. After all, the world only comes to life in response to the players' action (or inaction), which is then driven by their goals. Rewards give the players an indication of what they should be doing, generally speaking. At the same time, rewards are much more than mere incentives, which would lead players along a predesigned course. Rather, how the players go about achieving these rewards is unique to each group and to each story, and thus rewards must be open-ended. As mentioned in the previous article, players should always be given problems, not answers. How they answer problems is an expression of their freedom within the game world, and is the very narrative of the story itself.

Perhaps a good example of this can be seen in "Old Geezer" Mike Monard's fascinating on-going "tell-all" about the early days of Dungeons & Dragons. As he describes, experience awarded for defeating monsters in the Greyhawk dungeon was almost nothing, perhaps only enough to round off the experience gained from treasure, and that in his own games he does not reward any experience for monsters. The picture that immediately forms is one in stark contrast to modern "dungeon delving" games, with the players cast as "amoral mercenaries out to loot the dungeon," as one commenter put it. Where there is no reward, there is no risk-reward structure, and thus monsters are carefully avoided, like elite soldiers sneaking deep behind enemy lines in some subterranean fantasy Vietnam.

In the same way, a game that does not have a clearly identified reward structure is a game (and a game world) with an identity crisis. Without a framework of rewards (whether fame and fortune, or something else entirely), the players will not have a clear idea of what they should be doing. Without player action to fuel it, the world cannot come to life. This is probably one of the most discussed aspects of Dungeon World, still a work-in-progress, and several iterations of an "experience" system have been proposed (experience being one way to quantify reward).

One of the options that has gained the most traction, although not the current "official" solution, is Ryan Macklin's experiment. A hold-over from the primogenitor game Apocalypse World, this system has each player pick a basic strategy for another player to pursue that session (such as pulling stunts, defending others, acting diplomatically, solving possibles and so on). Each time the player acts accordingly, they earn experience, rewarding immediate and short term narrative styling. Thus, a Cleric (bidden to be more aggressive that session) will show a new angle to his character, as he beats the goblin he interrogates, or lashes out at his superiors in the monastery.

This is a fine system in itself, but perhaps more suited to the game it originated from (Apocalypse World is all about psychologically breaking characters down in a ruined world where no one is granted tomorrow). As forum-goer nemomeme points out, the reward structure determines what the very game is about. We must be careful to think about the essential design goals behind the game before tackling rewards.

So what is adventuring about? The very principles of Dungeon World (which make it so interesting and unique) demand that the fiction comes first. Like microgame adventures, the rules are discrete components that have specific triggers from the fiction, and are otherwise out of sight. The principles also state that the game is a conversation, so thus the rewards should also be in conversation. Perhaps a good model for reward, which is based on the fiction and also in constant conversation, would be Jeff Rient's article on "eXPloration".

Here, I can imagine players and referee discussing, as a group, what they want to do, as it comes up in the fiction. They could even create "experience ladders," listing some goals and objectives. Once players have achieved (or failed) all of their plans for a front (a living, breathing local situation), and the game master has no more moves to make, this should indicate that the front has been fully explored and the next expedition should be chartered. Each player might have a different list, but commonalities and overlaps are expected, as the party is acting within the same local area. An example might be:

• Find the slave camp deep in the jungle (+1 Exp)

• Defeat the Guaraxx lurking in the delta (+2 Exp)

• Get revenge on those pirates (+1 Exp)

• Discover what has made the villagers so frightened, and make it safe again (+2 Exp)

• Climb to the top of White Doom Mountain (+3 Exp)

• Spend a night in the Lost City (+1 Exp)

These goals are constantly being discussed, revised and traded as the fiction dictates, and represent paths of action parallel or tangential to the plot of the front. They give the players a clear idea of what this world is about (that is, the cool and amazing things to do and see, the supernatural adversity to overcome and the bonds to play off between players in the process). In fact, in many ways, this is merely an extension of the bonds rule from Dungeon World, which gives players an initial motivation before the first front is even encountered. Here, in addition to being bonded to each other, the players are bonded to the world. Most importantly, this method lets the fiction come first, which is an essential quality of Dungeon World, and a great deal of what makes it so unique.

Perhaps a good example of this can be seen in "Old Geezer" Mike Monard's fascinating on-going "tell-all" about the early days of Dungeons & Dragons. As he describes, experience awarded for defeating monsters in the Greyhawk dungeon was almost nothing, perhaps only enough to round off the experience gained from treasure, and that in his own games he does not reward any experience for monsters. The picture that immediately forms is one in stark contrast to modern "dungeon delving" games, with the players cast as "amoral mercenaries out to loot the dungeon," as one commenter put it. Where there is no reward, there is no risk-reward structure, and thus monsters are carefully avoided, like elite soldiers sneaking deep behind enemy lines in some subterranean fantasy Vietnam.

In the same way, a game that does not have a clearly identified reward structure is a game (and a game world) with an identity crisis. Without a framework of rewards (whether fame and fortune, or something else entirely), the players will not have a clear idea of what they should be doing. Without player action to fuel it, the world cannot come to life. This is probably one of the most discussed aspects of Dungeon World, still a work-in-progress, and several iterations of an "experience" system have been proposed (experience being one way to quantify reward).

One of the options that has gained the most traction, although not the current "official" solution, is Ryan Macklin's experiment. A hold-over from the primogenitor game Apocalypse World, this system has each player pick a basic strategy for another player to pursue that session (such as pulling stunts, defending others, acting diplomatically, solving possibles and so on). Each time the player acts accordingly, they earn experience, rewarding immediate and short term narrative styling. Thus, a Cleric (bidden to be more aggressive that session) will show a new angle to his character, as he beats the goblin he interrogates, or lashes out at his superiors in the monastery.

This is a fine system in itself, but perhaps more suited to the game it originated from (Apocalypse World is all about psychologically breaking characters down in a ruined world where no one is granted tomorrow). As forum-goer nemomeme points out, the reward structure determines what the very game is about. We must be careful to think about the essential design goals behind the game before tackling rewards.

So what is adventuring about? The very principles of Dungeon World (which make it so interesting and unique) demand that the fiction comes first. Like microgame adventures, the rules are discrete components that have specific triggers from the fiction, and are otherwise out of sight. The principles also state that the game is a conversation, so thus the rewards should also be in conversation. Perhaps a good model for reward, which is based on the fiction and also in constant conversation, would be Jeff Rient's article on "eXPloration".

Here, I can imagine players and referee discussing, as a group, what they want to do, as it comes up in the fiction. They could even create "experience ladders," listing some goals and objectives. Once players have achieved (or failed) all of their plans for a front (a living, breathing local situation), and the game master has no more moves to make, this should indicate that the front has been fully explored and the next expedition should be chartered. Each player might have a different list, but commonalities and overlaps are expected, as the party is acting within the same local area. An example might be:

• Find the slave camp deep in the jungle (+1 Exp)

• Defeat the Guaraxx lurking in the delta (+2 Exp)

• Get revenge on those pirates (+1 Exp)

• Discover what has made the villagers so frightened, and make it safe again (+2 Exp)

• Climb to the top of White Doom Mountain (+3 Exp)

• Spend a night in the Lost City (+1 Exp)

These goals are constantly being discussed, revised and traded as the fiction dictates, and represent paths of action parallel or tangential to the plot of the front. They give the players a clear idea of what this world is about (that is, the cool and amazing things to do and see, the supernatural adversity to overcome and the bonds to play off between players in the process). In fact, in many ways, this is merely an extension of the bonds rule from Dungeon World, which gives players an initial motivation before the first front is even encountered. Here, in addition to being bonded to each other, the players are bonded to the world. Most importantly, this method lets the fiction come first, which is an essential quality of Dungeon World, and a great deal of what makes it so unique.

Labels:

Campaigns,

Dungeon World,

Game Theory,

House Rules,

Settings

Friday, July 27, 2012

Worldsmiths

I wanted to expand a little on the previous discussion of campaign preparation. I do not believe a referee's preparation should look anything like a published adventure module, which were fixed and scripted scenarios developed specifically for the tournament milieu. These are, of course, fun to read for inspiration or to run the players through a "gauntlet" typical of gaming conventions. However, for home games, these adventures are far too scripted, and go against the basic principle that narration is neither controlled by referee nor by player (as discussed in the previous article).

Yet, it is imperative that the game world seems real and adventureful at every moment and in every scene. Some work must go into world creation, but this fashioning and shaping cannot have a stymying effect. The generative process must be continuous through the process of playing, so that the world comes alive and retains full fluidity. Player decisions, ever capricious, must remain meaningful.

Marshall Miller has given a good example of what this might look like for Dungeon World, a fan variant of Vincent Baker's Apocalypse World. That game already divides the environs of a game world into Fronts, which are living, breathing local situations that the players can get themselves mired in. Not only is a Front (e.g. the Caves of Chaos) a vivid and lush location to explore, but it is also an ambiguous, evil force to oppose the heroes, a ticking time bomb (with signs of the looming disaster), and a creature in and of itself (capable of executing its own moves and maneuvers against the players). A Front is a setting that truly comes to life, like the Mines of Moria, and opposes the heroes by its very nature. It must be carefully explored, discussed and negotiated by both the players and the referee alike, with the primary vehicle for this being dice rolls and decisions.

What Miller has added to this is the notion of the "Adventure Starter." This is another sort of environ in the game world, contained within a quick, flexible toolkit designed to spark the initial interest and action. An entire "Adventure Starter" environ consists in a reminder of the referee's guiding principles (make the world real, make it full of adventure etc), a list of scenic impressions to colour your descriptions and make the world real, some open-ended questions meant to both inspire sub-plots and to hook your players, a list of artifacts and creatures that might be of utility for the referee and finally a list of new moves open to the players while they explore the setting. Importantly, there are no maps, no pre-scripted story and no hard timelines. The referee could glance at the two-page setting and read as much or as little as he likes without missing anything important.

Both Fronts and Adventure Starters are an excellent way for a referee to prepare the environs and locales of the game world. They are inspirational and fluid, and may be used before and during the game to drive interesting scenes. At the same time, preparing this kind of gaming world is not about pre-establishing events, plots or geography. Those are answers, and the answers that the actual playing experience will give you are always better. Rather, the referee should start to think about preparing problems which do not necessarily have an answer… yet. Confronted with a living, dynamic and danger-filled world, the players' actions and words fill the adventure-engine that the referee has prepared, fueling gameplay that players can actually care about and feel.

Yet, it is imperative that the game world seems real and adventureful at every moment and in every scene. Some work must go into world creation, but this fashioning and shaping cannot have a stymying effect. The generative process must be continuous through the process of playing, so that the world comes alive and retains full fluidity. Player decisions, ever capricious, must remain meaningful.

Marshall Miller has given a good example of what this might look like for Dungeon World, a fan variant of Vincent Baker's Apocalypse World. That game already divides the environs of a game world into Fronts, which are living, breathing local situations that the players can get themselves mired in. Not only is a Front (e.g. the Caves of Chaos) a vivid and lush location to explore, but it is also an ambiguous, evil force to oppose the heroes, a ticking time bomb (with signs of the looming disaster), and a creature in and of itself (capable of executing its own moves and maneuvers against the players). A Front is a setting that truly comes to life, like the Mines of Moria, and opposes the heroes by its very nature. It must be carefully explored, discussed and negotiated by both the players and the referee alike, with the primary vehicle for this being dice rolls and decisions.

What Miller has added to this is the notion of the "Adventure Starter." This is another sort of environ in the game world, contained within a quick, flexible toolkit designed to spark the initial interest and action. An entire "Adventure Starter" environ consists in a reminder of the referee's guiding principles (make the world real, make it full of adventure etc), a list of scenic impressions to colour your descriptions and make the world real, some open-ended questions meant to both inspire sub-plots and to hook your players, a list of artifacts and creatures that might be of utility for the referee and finally a list of new moves open to the players while they explore the setting. Importantly, there are no maps, no pre-scripted story and no hard timelines. The referee could glance at the two-page setting and read as much or as little as he likes without missing anything important.

Both Fronts and Adventure Starters are an excellent way for a referee to prepare the environs and locales of the game world. They are inspirational and fluid, and may be used before and during the game to drive interesting scenes. At the same time, preparing this kind of gaming world is not about pre-establishing events, plots or geography. Those are answers, and the answers that the actual playing experience will give you are always better. Rather, the referee should start to think about preparing problems which do not necessarily have an answer… yet. Confronted with a living, dynamic and danger-filled world, the players' actions and words fill the adventure-engine that the referee has prepared, fueling gameplay that players can actually care about and feel.

Tuesday, July 17, 2012

Say No or Force Them to Make a Saving Throw Versus Death

Flipping through Diaspora yesterday, I came across a sentiment increasingly common to modern roleplaying games. At the core of Diaspora (and many such newer games) is the phrase "Say Yes, or Roll the Dice." Essentially, this axiom requires the referee to always endorse the players' proposed strategy, or at least give them a shot with a die roll.

For Fate fans (which includes Diaspora, Spirit of the Century, Legends of Anglerre and many other related games), this has been heralded as a very "tactical" system. Players are constantly coming up with spur of the moment plans (actually, justifications for why they should win), which the referee must then accept, or let the dice decide. It is reminiscent of old school procedure, where the referee listens to the plan carefully and then comes up with a target number and rolls the die to determine success. The only difference is that "Say Yes…" precludes the referee's veto. The referee is instead slavishly committed to accepting every player strategy, regardless of how believable it is, or how it circumvents the referee's own schemes. Rather than staging a tactical opposition, the referee is subject to player whim.

This is, perhaps, seen as contrasting adversarial-style refereeing. It also developed, however, in response to a style of Dungeons & Dragons that increasingly defined characters by "Player Options," "Powers" and other mechanical advantages. Instead of thinking through a problem, players would simply look down at their character sheet for all the answers. Written in 2002 at the height of the third edition, The Burning Wheel fantasy roleplaying game was, in many ways, a response to what Dungeons & Dragons had become. In contrast with a referee-dominated narrative and players with mechanically enabling character powers, The Burning Wheel introduced the "Say Yes…" paradigm for the first time, and thus framed the referee as an enabler and the players as holding narrative control.

Of course, buying into this premise of "player control versus referee control" has obscured the original simple and elegant functionality of Dungeons & Dragons. Recently, I asked Mike Monard (veteran of the original Lake Geneva campaign) whether referees back in the day would punish Magic-Users who neglected utility spells and front-loaded combat spells by throwing in obstacles that would require the former. His response was illuminating, and is worth quoting here in full:

"Remember… the world was created first, THEN the characters were created to explore it. The way Gary, Dave, and the rest of us did it, we would set up our dungeons such that you would need a selection of both combat and utility spells. Choosing how to allocate your limited spell slots was part of the fun, as was dealing with not having a certain spell where it would be useful.

The world came first, so changing the world based on player spell selection would have been cheating. It's about the only way for the referee to cheat, in fact. Any ref who changed things on the fly to punish players based on that day's spell selection would have found themselves without any players.

What was there, was there. There was a nest of six trolls on Level 1 of Greyhawk. If you went there with three first level characters, you found six trolls. If you went there with nine 11th level characters, you found six trolls. Changing the world as you seem to be describing above would have been anathema. It is really the only way to cheat as the referee."

The referee developed a world, the players investigated it, and changing things after the fact was cheating. It was part and parcel of suspension of disbelief that the world followed its own laws and trajectory. How player decisions might intersect with that trajectory was largely unpredictable, and there was a level of excitement and discovery for both players and referee. There is a classic movement here which is common to Shakespeare plays, whereby one person would pass partial information along to another individual, who would then filter it further to a third. Consider the Doctor who agrees to provide the Queen with a vial of poison but, fearing her evil designs, actually gives her a sleeping draught. The Queen, thinking the elixir to be a poison, hands it further to the naive rival princess, promising that it is a healing balm to be taken when she is feeling ill. The King falls ill and the princess administers the sleeping draught. Chaos ensues.

Likewise, the referee may know what is really going on, but this is filtered through interrogated non-player characters or partial clues that the players may find. Only half of the truth reaches the players, who then introduce a further (and unpredictable) abstraction through their misinterpretation of the situation. This beautiful friction makes for the stuff of true legends. Here, the referee is neither adversarial nor enabling, but rather purely neutral (which reminds me of an excellent and illustrative Knights of the Dinner Table comic, where the Knights are able to "outsmart" B.A.'s flagship dungeon).

The take away from all of this is that we as referees must again become world-smiths. It is hard work, and tremendous preparation must go into the campaign as well as each individual session. Different webs of non-player characters must be charted, including individual motives and knowledge. Interesting eventualities must be at least initially considered, while some obstacles with no apparent solution should be cataloged (perhaps a dungeon at the top of a perfectly sheer cliff, encouraging the players to be creative). The story will take unexpected turns, and the referee's encyclopedic register of history and dramatis personae will breath enough life into the world that it will take on its own momentum. In all of this, narrative control belongs to the friction between player knowledge and referee impartiality. As the authors of Adventurer Conqueror King put it, "every campaign is a law unto itself" and the excitement comes from these worlds taking on a life of their own.

For Fate fans (which includes Diaspora, Spirit of the Century, Legends of Anglerre and many other related games), this has been heralded as a very "tactical" system. Players are constantly coming up with spur of the moment plans (actually, justifications for why they should win), which the referee must then accept, or let the dice decide. It is reminiscent of old school procedure, where the referee listens to the plan carefully and then comes up with a target number and rolls the die to determine success. The only difference is that "Say Yes…" precludes the referee's veto. The referee is instead slavishly committed to accepting every player strategy, regardless of how believable it is, or how it circumvents the referee's own schemes. Rather than staging a tactical opposition, the referee is subject to player whim.

This is, perhaps, seen as contrasting adversarial-style refereeing. It also developed, however, in response to a style of Dungeons & Dragons that increasingly defined characters by "Player Options," "Powers" and other mechanical advantages. Instead of thinking through a problem, players would simply look down at their character sheet for all the answers. Written in 2002 at the height of the third edition, The Burning Wheel fantasy roleplaying game was, in many ways, a response to what Dungeons & Dragons had become. In contrast with a referee-dominated narrative and players with mechanically enabling character powers, The Burning Wheel introduced the "Say Yes…" paradigm for the first time, and thus framed the referee as an enabler and the players as holding narrative control.

Of course, buying into this premise of "player control versus referee control" has obscured the original simple and elegant functionality of Dungeons & Dragons. Recently, I asked Mike Monard (veteran of the original Lake Geneva campaign) whether referees back in the day would punish Magic-Users who neglected utility spells and front-loaded combat spells by throwing in obstacles that would require the former. His response was illuminating, and is worth quoting here in full:

"Remember… the world was created first, THEN the characters were created to explore it. The way Gary, Dave, and the rest of us did it, we would set up our dungeons such that you would need a selection of both combat and utility spells. Choosing how to allocate your limited spell slots was part of the fun, as was dealing with not having a certain spell where it would be useful.

The world came first, so changing the world based on player spell selection would have been cheating. It's about the only way for the referee to cheat, in fact. Any ref who changed things on the fly to punish players based on that day's spell selection would have found themselves without any players.

What was there, was there. There was a nest of six trolls on Level 1 of Greyhawk. If you went there with three first level characters, you found six trolls. If you went there with nine 11th level characters, you found six trolls. Changing the world as you seem to be describing above would have been anathema. It is really the only way to cheat as the referee."

The referee developed a world, the players investigated it, and changing things after the fact was cheating. It was part and parcel of suspension of disbelief that the world followed its own laws and trajectory. How player decisions might intersect with that trajectory was largely unpredictable, and there was a level of excitement and discovery for both players and referee. There is a classic movement here which is common to Shakespeare plays, whereby one person would pass partial information along to another individual, who would then filter it further to a third. Consider the Doctor who agrees to provide the Queen with a vial of poison but, fearing her evil designs, actually gives her a sleeping draught. The Queen, thinking the elixir to be a poison, hands it further to the naive rival princess, promising that it is a healing balm to be taken when she is feeling ill. The King falls ill and the princess administers the sleeping draught. Chaos ensues.

Likewise, the referee may know what is really going on, but this is filtered through interrogated non-player characters or partial clues that the players may find. Only half of the truth reaches the players, who then introduce a further (and unpredictable) abstraction through their misinterpretation of the situation. This beautiful friction makes for the stuff of true legends. Here, the referee is neither adversarial nor enabling, but rather purely neutral (which reminds me of an excellent and illustrative Knights of the Dinner Table comic, where the Knights are able to "outsmart" B.A.'s flagship dungeon).

The take away from all of this is that we as referees must again become world-smiths. It is hard work, and tremendous preparation must go into the campaign as well as each individual session. Different webs of non-player characters must be charted, including individual motives and knowledge. Interesting eventualities must be at least initially considered, while some obstacles with no apparent solution should be cataloged (perhaps a dungeon at the top of a perfectly sheer cliff, encouraging the players to be creative). The story will take unexpected turns, and the referee's encyclopedic register of history and dramatis personae will breath enough life into the world that it will take on its own momentum. In all of this, narrative control belongs to the friction between player knowledge and referee impartiality. As the authors of Adventurer Conqueror King put it, "every campaign is a law unto itself" and the excitement comes from these worlds taking on a life of their own.

Thursday, July 12, 2012

Every Fighting-Man is Unique

I am not aware when it came about, but at some point a vicious rumour crept into our collective understanding of Dungeons & Dragons. This rumour subtly, surreptitiously put forth the notion that the original game, in its basic, open-ended template form, was somehow too limited. There weren't enough monsters, there weren't enough classes, there weren't enough powers or abilities. The original game, so this shadowy speculation would have you believe, just didn't have enough stuff.

So the next generation of more "advanced" games came out, promising more things for the throngs of adventure-hungry players to do by promising game rules that were packed with more stuff. Ironically, on the other end of this history (some thirty years later), we are now flooded with such games—enough to stack from floor to ceiling in a dusty, unvisited brick-and-mortar gaming store. We certainly have enough adventure, yet, we have very few players hungry for adventure. What went wrong? What was it that originally enchanted those players, who came from every walk of life, and made them so esurient?

Today's games have naturally attracted a very different, and far less diverse crowd (which is unfortunate, not only because we lose perspective and creativity, but because many of the so-called "gamers" are individuals that no one in their right mind would like to spend an afternoon with). The excessive influx of systems, mechanics and rules to our Saturday afternoon scenarios naturally caters to rules-obsessed types, and the move away from free-form, communal decision-making and storytelling alienates people who didn't sign up for this level of commitment. But there is also a delightful agility that was somehow lost in this sad transmutation.

I believe that earlier adventuring aficionados truly understood that the original game was merely a template. The apparent limitation, for example, to choose one of three iconic character options (Fighting-Man, Magic-User or Cleric) belies the fact that these choices were never meant as more than basic blueprints from which characters were built. Looking in the three little books, for instance, one finds extremely few limitations: ability scores have next to no impact on the game, the rules allow dual and multi-classing, and any character can attempt any action. There was essentially an adventurer, and different options determined what access he or she had to different equipment and spellcraft.

One of the rarely highlighted aspects of the original game in particular is the concept of level titles. This dizzying array of honorifics is typically understood as a strict progression, one to the next, so that a Hero becomes a Swashbuckler or a Sorcerer becomes a Necromancer or a Bishop becomes a Lama. Yet, as we can see, this progression is not altogether coherent (why should a Catholic Bishop become a Tibetan Lama, exactly?), which may have led many to simply discard level titles entirely. At my table, I encourage my players to really make level titles their own, however, and use them to define their characters.

Maybe Toki, a Japanese Fighting-Man character, starts off as a Veteran. By level two, I encourage him to describe how his Fighting-Man is different, and soon he takes the level two title "Sohei" (or warrior monk, becoming an ascetic mountain warrior). During level two, I allow him to track monsters through the woods or navigate untamed mountains. By level three, the campaign has taken another turn: Toki takes on the role of a pirate and starts swinging from ropes and intimidating his opponents.

Customizing level titles is an excellent way to show your players that the archetypal classes are merely base templates from which characters are developed. I do not believe a party with 14 Fighting-Men should feel like a party with 14 Fighting-Men. The fact is that the Fighting-Man class, like the other classes, is broad enough to contain every sword-swinging hero one could dream up. Each character should be different and unique, and the rules of the original game are just open-ended enough to allow that. In reality, there is nothing more alienating than bringing a new player to your table and telling him that his character concept has to fit within your game's hard boundaries and strict definitions, and this is one of the main reasons that this hobby lost its diverse player community: we stopped asking people to bring their own creativity and ideas to the table.

So the next generation of more "advanced" games came out, promising more things for the throngs of adventure-hungry players to do by promising game rules that were packed with more stuff. Ironically, on the other end of this history (some thirty years later), we are now flooded with such games—enough to stack from floor to ceiling in a dusty, unvisited brick-and-mortar gaming store. We certainly have enough adventure, yet, we have very few players hungry for adventure. What went wrong? What was it that originally enchanted those players, who came from every walk of life, and made them so esurient?

Today's games have naturally attracted a very different, and far less diverse crowd (which is unfortunate, not only because we lose perspective and creativity, but because many of the so-called "gamers" are individuals that no one in their right mind would like to spend an afternoon with). The excessive influx of systems, mechanics and rules to our Saturday afternoon scenarios naturally caters to rules-obsessed types, and the move away from free-form, communal decision-making and storytelling alienates people who didn't sign up for this level of commitment. But there is also a delightful agility that was somehow lost in this sad transmutation.

I believe that earlier adventuring aficionados truly understood that the original game was merely a template. The apparent limitation, for example, to choose one of three iconic character options (Fighting-Man, Magic-User or Cleric) belies the fact that these choices were never meant as more than basic blueprints from which characters were built. Looking in the three little books, for instance, one finds extremely few limitations: ability scores have next to no impact on the game, the rules allow dual and multi-classing, and any character can attempt any action. There was essentially an adventurer, and different options determined what access he or she had to different equipment and spellcraft.

One of the rarely highlighted aspects of the original game in particular is the concept of level titles. This dizzying array of honorifics is typically understood as a strict progression, one to the next, so that a Hero becomes a Swashbuckler or a Sorcerer becomes a Necromancer or a Bishop becomes a Lama. Yet, as we can see, this progression is not altogether coherent (why should a Catholic Bishop become a Tibetan Lama, exactly?), which may have led many to simply discard level titles entirely. At my table, I encourage my players to really make level titles their own, however, and use them to define their characters.

Maybe Toki, a Japanese Fighting-Man character, starts off as a Veteran. By level two, I encourage him to describe how his Fighting-Man is different, and soon he takes the level two title "Sohei" (or warrior monk, becoming an ascetic mountain warrior). During level two, I allow him to track monsters through the woods or navigate untamed mountains. By level three, the campaign has taken another turn: Toki takes on the role of a pirate and starts swinging from ropes and intimidating his opponents.

Customizing level titles is an excellent way to show your players that the archetypal classes are merely base templates from which characters are developed. I do not believe a party with 14 Fighting-Men should feel like a party with 14 Fighting-Men. The fact is that the Fighting-Man class, like the other classes, is broad enough to contain every sword-swinging hero one could dream up. Each character should be different and unique, and the rules of the original game are just open-ended enough to allow that. In reality, there is nothing more alienating than bringing a new player to your table and telling him that his character concept has to fit within your game's hard boundaries and strict definitions, and this is one of the main reasons that this hobby lost its diverse player community: we stopped asking people to bring their own creativity and ideas to the table.

Thursday, June 21, 2012

What is a Setting?

Campaign settings have always held a rather schizophrenic place in this hobby. The first settings, Blackmoor and Greyhawk, were merely the dungeon and the environs around it, extending further only rarely, as the adventurers pursued other plots (and then collapsing back to the central dungeon when new players came in). A great example of this are the adventures of Robliar, Tenser and Erac, who dropped through the chute to China in the ruined pile of Greyhawk Castle, only to adventure back to the other side of the world, drawn like a magnet to the tentpole of the campaign. Other campaign events created new areas, such as the domain of Iuz (a foe who was originally released from the dungeons of Greyhawk), yet these new area always deferred to the original environs (with no sustained campaigning in the new regions).

Campaign settings have always held a rather schizophrenic place in this hobby. The first settings, Blackmoor and Greyhawk, were merely the dungeon and the environs around it, extending further only rarely, as the adventurers pursued other plots (and then collapsing back to the central dungeon when new players came in). A great example of this are the adventures of Robliar, Tenser and Erac, who dropped through the chute to China in the ruined pile of Greyhawk Castle, only to adventure back to the other side of the world, drawn like a magnet to the tentpole of the campaign. Other campaign events created new areas, such as the domain of Iuz (a foe who was originally released from the dungeons of Greyhawk), yet these new area always deferred to the original environs (with no sustained campaigning in the new regions).Yet, when TSR took off, it became profitable to publish fully detailed and designed campaign backdrops. World maps were drawn up for the first time ever, and the local environs around Castle Greyhawk became the "World of Greyhawk" (true, the original Greyhawk was situated on the C&C Society map, but the extent of this map is unknown and apparently not well developed). With published settings, the concept of a campaign backdrop turned from the small, local region to the internation and global scene.

Still, I suspect, most referees ended up designing their own settings for their home campaigns, much like Arneson and Gygax themselves had done. The natural impulse is not to delineate a sweeping world, painting with a broad brush, but rather to go ever smaller, refining the details and going deeper into the very concept of the setting. The former approach is geographic, and creates boundaries that delimit thought even as the "broad approach" is meant to liberate possibilities by making the world seem "big." The latter approach is conceptual, and defines the setting as an idea, not a fixed and stale cartography where the possibility for new events must be fit into a pre-existing framework. They are fundamentally different approaches, one structural and the other theoretical, that produce very different experiences for the referee (and we must remember that the referee is a player too, and that campaign preparation is part of the game).

Interestingly, it was setting stagnation (and setting over-definition), that first drove Arneson to boredom with Braunstein, leading him to create Blackmoor. The Napoleonic scenario had been fully described and defined, and the possibilities exhausted, by a structural approach to the scenario that put characters in relation to each other like chess pieces. Instead of focusing on the politics of the scenario, however, Blackmoor focused on the root inspiration at the core of the setting. As the DCC rulebook says:

"Make your world mysterious by making it small—very small. What lies past the next valley? None can be sure. When a five-mile journey becomes an adventure, you'll have succeeded in bringing life to your world." (Dungeon Crawl Classics Roleplaying Game, page 314)

Here, the sage advice to "think local" should be paired with a conceptual approach to campaign definition. There is world enough in the 50 miles around your central megadungeon: make things happen there! Festivals are thrown, distant merchants arrive, new enemies appear, alliances are struck and broken. The core concept of your campaign inspiration is often difficult to articulate, but one should not flee from this and start detailing regions that no player will likely ever see. Instead, turn back and develop that core concept more and more, mining it for new inspiration, and do not be afraid to let it change as your interests (or real events from the campaign) require. No one truly knows where such a setting will go next, yet it always feels like home.

Sunday, June 17, 2012

New Gary Gygax Setting

I don't usually do this, especially after my recent rant about Kickstarters that "over-promise," but I have to make an exception for John Adams' (of Brave Halfling Publishing fame) new project, the Appendix N Adventure Toolkits. Unlike some of the lest-tested indie publishers, who are riding on the coattails of OSR-Kickstarter craze, I know Brave Halfling's work well and have a lot of trust in John's ability. He's been around for quite a while now, and I even own some of his early publications for Castles & Crusades, Swords & Wizardry and Labyrinth Lord. He has been behind a lot of truly excellent products, like the "Old School Gaming Box," Delving Deeper (the original Dungeons & Dragons reprint with Rob Conley's Blackmarsh) and Perilous Mazes (the Holmes Basic Dungeons & Dragons reprint).

I don't usually do this, especially after my recent rant about Kickstarters that "over-promise," but I have to make an exception for John Adams' (of Brave Halfling Publishing fame) new project, the Appendix N Adventure Toolkits. Unlike some of the lest-tested indie publishers, who are riding on the coattails of OSR-Kickstarter craze, I know Brave Halfling's work well and have a lot of trust in John's ability. He's been around for quite a while now, and I even own some of his early publications for Castles & Crusades, Swords & Wizardry and Labyrinth Lord. He has been behind a lot of truly excellent products, like the "Old School Gaming Box," Delving Deeper (the original Dungeons & Dragons reprint with Rob Conley's Blackmarsh) and Perilous Mazes (the Holmes Basic Dungeons & Dragons reprint).His latest effort, however, is stunning. While it started out as simply a single, low-level module, the Appendix N Adventure Toolkits has surpassed my expectations. I find it somewhat difficult to interpret Kickstarters sometimes, so I will break it down for those who haven't had a chance to check this project out yet. After breaking four stretch goals, the project is now giving each supporter (at the paltry $20 level): a PDF copy of each of the five full adventure modules (one of the scenarios which will never be released again), a digest print copy of each of the same (each signed, numbered and shrink wrapped), a poster to hang up in your den and a special edition box to store the modules. For an extra $10, you get a second copy of each module (I guess one would be a play copy and the other a keeper? Or maybe a gift to your nephew to get him into roleplaying?) and eight (8!) more PDFs of new rules and options for DCC characters and classes.

This is really a fantastic value, and a very neat idea to boot (especially the collector's box for storing everything), and the artwork previews already released are top-notch. However, what caught my attention in the first place was the next stretch goal: an original setting developed by John Adams and Gary Gygax through their correspondences. This unpublished work was going to be for Gary's last game, Lejendary Adventures, but came to a halt with his passing. While I never thought Gary was the best game designer, his worlds have always inspired me, and I have found him to be quite a wordsmith when drawing up an old-school setting. Now, if this project gets enough funders, anyone who puts in that same paltry $20 donation will get a sixth print and PDF, "The Old Isle Campaign Setting," in addition to a color poster map of the setting. I cannot be alone in finding it a shame to leave this final work undiscovered, which was written by Adams, but with the keen editing and insight of the original Dungeon Master. Count me interested and in support of this project.

Friday, June 15, 2012

SUPER OD&D

Marv made an interesting comparison over on the Goodman Games boards. To me, Dungeon Crawl Classics is like a Super OD&D (in the tradition of Super Mario Brothers games). Indeed, it has many similarities to the three little brown books of the original game, yet it makes thewy additions and expansions to that base as well. The first volume of that game alone shares basic assumptions about the social scale of experience levels, the power of classes, the protected niches of characters, the nature of magic.

Marv made an interesting comparison over on the Goodman Games boards. To me, Dungeon Crawl Classics is like a Super OD&D (in the tradition of Super Mario Brothers games). Indeed, it has many similarities to the three little brown books of the original game, yet it makes thewy additions and expansions to that base as well. The first volume of that game alone shares basic assumptions about the social scale of experience levels, the power of classes, the protected niches of characters, the nature of magic.Take magic, for example. Via Chainmail, the magic system in the original game is highly unpredictable, where magic-users can cast a spell only to find their spell miscast without benefit (and lost), cast successfully (and retained for future use) or caught somewhere in between, in limbo until the next turn. DCC takes this basic principle and adds much more detail, so that miscast spells might also transform the caster into a hideous creature, or successful sorcery might prove unexpectedly powerful. Add in supernatural patrons and character-specific spell manifestations and you have a magic system that is built from the same basic foundation as OD&D, yet with much more muscle to it.

Similarly, the progression of power for fighting-men is modelled directly on OD&D. While later "advanced" editions of the game weakened the fighter, introducing the "linear fighter, quadratic wizard" quandry, it is important to remember that this problem is entirely foreign to the original three little booklets. A ninth level fighting-man was simply nine times more powerful than when he first started out (similarly so for magic-users). He fought as nine men, with nine attacks (each the strength of one man's strike). While his "advanced" cousing, the fighter of AD&D was reduced to two or three attacks a round, the DCC warrior returns to native soil in a unique way, making three attacks, each strike the strength of three men (for identical output to the OD&D fighting-man, but with less dicing). Add in critical hit charts, fumbles and mighty deeds, and again you have a robust and powerful addition to the original game.

Even the social scale of characters in DCC is reminiscent of the original game, where a first level warrior is no mere soldier. Roughly speaking, a first level character is already the hero of the townships, an unlikely local that rose to unexpected prominence for his deeds. His tales will be told in the few villages of the valley for several generations. A level two character is the celebrity of a major city, well known by all but the unsophisticated. By third level, an adventurer has already rose to the prestige of a conqueror-king or slayer, whose legend will endure. This is far removed from the scale of power in later games, but is actually perfectly in line with the concepts found in OD&D.

More comparisons can, of course, be drawn with the other volumes, but this is just what comes to mind while paging through Men & Magic. I am curious how this plays out over longterm play, but I suspect the pace and style of DCC would be very reminiscent of the original three little books. Of course, it was always a design goal of DCC, it seems, to start at 1974, but only go backwards from there, instead of forward into the future.

Saturday, June 2, 2012

Kickstarter

It's raining today. I'm in the home stretch of working at perhaps my second worst job (I worked at a nursing home when I was a teenager, which takes the cake by far). I always love the rain—gusting about and dreary. It reminds me of a vacation in Ireland from my childhood, where I first walked wide-eyed into a small, bright store. "Games Workshop." I didn't know what they all were for, lining the walls and display cases, but I left with a promo magazine and nearly spent the rest of the trip staring intently at one particular picture of rank-and-file Wood Elf spearmen defending a dark forest.

I worked all the next summer at my first job, earning $3.15 an hour on a neighbor's farm (I had to haggle to get that extra 15¢). I was there from 6am to 4pm, shoveling hills of manure to a location 3 feet away, running away from homicidal stampedes of dairy cows, and finding lucky cowbells in the tall weeds (long story). After the summer, I picked up the well-worn brochure again and called the number on the back.

That was my first fantasy gaming purchase. The next high point would come in 2005, when I accidentally chanced upon a dusty copy of HackMaster 4th Edition in a store. It perfectly captured everything I loved about AD&D (I had been indirectly led to 2nd Edition through Warhammer Fantasy Battle). I loved this unlikely hobby. I found there was nothing else like it, nothing which created a whole new world within my daily imaginings. And I loved working for that, and buying into that. Pen and paper gaming, whether wargaming or roleplaying, became the satisfyingly open-ended, undefined daydreaming that buouyed me in the work-a-day world that it so contrasted. As the tongue-in-cheek call to arms on the back cover of the HackMaster Player's Handbook read:

"For those of us that live in a world that forces us to conform, to abide by the rules day in and day out; for those of us that suffocate in our daily routine of breakfast cereal and ham sandwiches; for those of us that slave each day in our cubicle working for the Man; those who would be heroes if it weren't for the constraints of reality, we present:"

Websites, forums and online communities only entered into that picture later. I didn't even realize Games Workshop had a website in the beginning, and used to order completely from printed catalogs, referencing only small, grey photos to specify with the ever-patient sales rep exactly which Wood Elf spearmen poses I wanted. There was a sense of adventure in not knowing everything that was going on in the industry, or not knowing about everything that was due to release soon. The possibilities were endless, and the frontiers of that world mysterious. I was happily in a bubble, and eager for every new bit of news that was so hard-won at the time.

Crowd-funding has changed a lot about the indie publishing industry. Yet (and I hate to be the first one to suggest it, as it seems to be breathing such real, quantifiable life ($) into the scene), I suspect there is a bubble here that is close to popping. Indeed, game designers have taken to crowd-funding largely because there is no current technology for making traditional publishing-distribution chains viable for niche markets. Like Google Checkouts, Kickstarter (et al.) allows reliable direct sale opportunities for small publishers that have been largely shut out by conservative distributors. But what cost is there for this immediacy? Niche hobbies thrive on interest, but while everyone seems to be excited about stretch goals, interactive product development and tiered reward levels, I can't help but feel that some of the magic has been taken out of the process.

As consumers, we are getting a lot of direct information through participating in funding, whether in the form of special sneak peaks, previews of potential new products or simply some small part in sharing the product design. But more interaction, and more information, is not always a good thing. I can imagine a Kickstarter burnout in the future, where the excitement that crowd-funding pre-orders generate is overtaken by information overload. A burnout where our building interest in seeing a project as it developes dissapates a little more when we finally receive the product we have been over-expecting. Crowd-funding means you are paying ahead for a product that you will not have in your hands for many months. Even with great products, what is the evaporation rate of that excitement that must survive that long stretch?

There are other problems with crowd-funding as well. It seems to be accelerating the already miserable state of distribution, pushing local gaming stores further to the fringes, and increasingly moving communities online. One of our local Islamic scholars here in Toronto remarked about that final point just last weekend, while speaking before a (traditional) dinner fundraiser for his school. In reference to online education, he argued that it is ironic that online communities are supposedly all about connecting with each other, while in reality they leave us more practically disconnected than ever before.

I don't really have another answer, and simply saying "well, the glory days of roleplaying games are over" and letting the entropy of distribution set in seems passé. Kickstarter et al. seems to have breathed new monetary life into the OSR, but let's not forget that the OSR began well before industrious-types had figured out a way to capitalize it. It was carried then by traditional enthusiasm of tangible substance. While websites like Kickstarter have been proven to generate hype, at the end of the day, the enduring proofs in this hobby are quality products on the one hand, and an abiding sense of mystery on the other. Unfortunately, crowd-funding tends to be antithetical to both ends, as it creates a very low barrier for self-publishing, while also flushing out the entire discourse of what makes a satisfying roleplaying game product into terms of what is immediately gratifying. Even then, with the nature of project funding, the immediate gratification of spoilers, previews and shared development are only deceptively immediate, creating dangerous over-anticipation.

I worked all the next summer at my first job, earning $3.15 an hour on a neighbor's farm (I had to haggle to get that extra 15¢). I was there from 6am to 4pm, shoveling hills of manure to a location 3 feet away, running away from homicidal stampedes of dairy cows, and finding lucky cowbells in the tall weeds (long story). After the summer, I picked up the well-worn brochure again and called the number on the back.

That was my first fantasy gaming purchase. The next high point would come in 2005, when I accidentally chanced upon a dusty copy of HackMaster 4th Edition in a store. It perfectly captured everything I loved about AD&D (I had been indirectly led to 2nd Edition through Warhammer Fantasy Battle). I loved this unlikely hobby. I found there was nothing else like it, nothing which created a whole new world within my daily imaginings. And I loved working for that, and buying into that. Pen and paper gaming, whether wargaming or roleplaying, became the satisfyingly open-ended, undefined daydreaming that buouyed me in the work-a-day world that it so contrasted. As the tongue-in-cheek call to arms on the back cover of the HackMaster Player's Handbook read:

"For those of us that live in a world that forces us to conform, to abide by the rules day in and day out; for those of us that suffocate in our daily routine of breakfast cereal and ham sandwiches; for those of us that slave each day in our cubicle working for the Man; those who would be heroes if it weren't for the constraints of reality, we present:"

Websites, forums and online communities only entered into that picture later. I didn't even realize Games Workshop had a website in the beginning, and used to order completely from printed catalogs, referencing only small, grey photos to specify with the ever-patient sales rep exactly which Wood Elf spearmen poses I wanted. There was a sense of adventure in not knowing everything that was going on in the industry, or not knowing about everything that was due to release soon. The possibilities were endless, and the frontiers of that world mysterious. I was happily in a bubble, and eager for every new bit of news that was so hard-won at the time.

Crowd-funding has changed a lot about the indie publishing industry. Yet (and I hate to be the first one to suggest it, as it seems to be breathing such real, quantifiable life ($) into the scene), I suspect there is a bubble here that is close to popping. Indeed, game designers have taken to crowd-funding largely because there is no current technology for making traditional publishing-distribution chains viable for niche markets. Like Google Checkouts, Kickstarter (et al.) allows reliable direct sale opportunities for small publishers that have been largely shut out by conservative distributors. But what cost is there for this immediacy? Niche hobbies thrive on interest, but while everyone seems to be excited about stretch goals, interactive product development and tiered reward levels, I can't help but feel that some of the magic has been taken out of the process.

As consumers, we are getting a lot of direct information through participating in funding, whether in the form of special sneak peaks, previews of potential new products or simply some small part in sharing the product design. But more interaction, and more information, is not always a good thing. I can imagine a Kickstarter burnout in the future, where the excitement that crowd-funding pre-orders generate is overtaken by information overload. A burnout where our building interest in seeing a project as it developes dissapates a little more when we finally receive the product we have been over-expecting. Crowd-funding means you are paying ahead for a product that you will not have in your hands for many months. Even with great products, what is the evaporation rate of that excitement that must survive that long stretch?

There are other problems with crowd-funding as well. It seems to be accelerating the already miserable state of distribution, pushing local gaming stores further to the fringes, and increasingly moving communities online. One of our local Islamic scholars here in Toronto remarked about that final point just last weekend, while speaking before a (traditional) dinner fundraiser for his school. In reference to online education, he argued that it is ironic that online communities are supposedly all about connecting with each other, while in reality they leave us more practically disconnected than ever before.

I don't really have another answer, and simply saying "well, the glory days of roleplaying games are over" and letting the entropy of distribution set in seems passé. Kickstarter et al. seems to have breathed new monetary life into the OSR, but let's not forget that the OSR began well before industrious-types had figured out a way to capitalize it. It was carried then by traditional enthusiasm of tangible substance. While websites like Kickstarter have been proven to generate hype, at the end of the day, the enduring proofs in this hobby are quality products on the one hand, and an abiding sense of mystery on the other. Unfortunately, crowd-funding tends to be antithetical to both ends, as it creates a very low barrier for self-publishing, while also flushing out the entire discourse of what makes a satisfying roleplaying game product into terms of what is immediately gratifying. Even then, with the nature of project funding, the immediate gratification of spoilers, previews and shared development are only deceptively immediate, creating dangerous over-anticipation.

Monday, May 28, 2012

Cosmic Alignment

John (of Thistledown Post) put up an interesting discussion on alignment in the DCC RPG. As he relates...

"The system of alignment in the DCC RPG is one that reflects its old-school heritage... Law is given as the choice of those who would uphold society's system of order and rules, producing the common good. Chaos is all about over-throwing authority, exercising personal power, and self-serving ends. The middle ground is Neutrality, the choice of those who choose not to decide, (hmmm...sounds like a famous Rush song of which I'm fond.)"

It is interesting that DCC specifically chooses not to equate Law with "good" and Chaos with "evil." Point in fact, the DCC RPG core book describes bugbears, goblins, hobgoblins, and troglodytes as being Lawful, and thus vulnerable to be Turned by chaotic Clerics. It is undoubtedly surprising to some that such traditionally evil creatures would be categorically Lawful in alignment, until you consider that there may be multiple axes that the struggles of the "urth" orbit around. Morality and Order are two such axes that do not necessarily always converge, as they have their own alien interests and objectives. Rather than seen as a graph or chart, perhaps aligning morality with order is better seen as a complex gyroscope, where good and evil is one ring and law and order are another (where even further alignments, include political, planar and magical could be included).

Certainly, neither pole of order (Law or Chaos) apparently comports itself to morality. As John describes:

"In my campaign, Law and Chaos will be struggling for dominance. Either potential outcome will not be good for the mortal folks of the world. If Law wins, the world become stagnant and unmoving. If Chaos wins, the world becomes a place of ever-changing pain and torment."

As the sun burns away and the old stars draw ever closer, ethics are increasingly merely short term sources of guidance. In truth, the dominion of either Law or Chaos will have an ultimately tyranical effect that will blot out all life. Law will crush its own people under heel, or simply allow them to die out and fade away in a perfect utopia, doomed by entropy like Tolkien's elves. Chaos will turn the world over into rioting and ruin. Neutral forces are aligned to the very passage of time itself, and seek either to prolong the titanic struggle that lays waste to the urth as long as possible before the imminent and inevitable end, or are entirely uninterested in the world's fate and worship the very fatality of it all. Dread Cthulhu, who would mindlesly tear the urth to pieces like a wet paper towel were he ever to turn over in his sleep, is notably Neutral in the DCC RPG book.

What I like here is that morality is something that veils the perhaps less obvious, but in the long term more dire, conflict. Morality concerns itself with the present, contingent and earthly situation, and represents an entirely different axis that intersects at times with Law and Chaos, which are more cosmic in origin. Ultimately, it is the ancient struggle between the latter forces, however, that march the world ever closer to inexorable collapse.

Here, the world is never to be saved, and the downfall is more or less inevitable. The urth is doomed, and stands in the shadows of a late age where the powers of order have long since committed to mutually assured destruction. This long tide from the deep oceans of the cosmos is drawing in upon the tiny urth, and will wash over its edifices and civilizations.

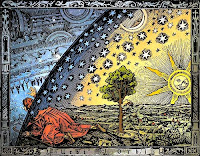

We can start to see a convergence between the concept of different planes of existence and the different interpretations of alignment (which has been, at times, a stand in for morality, psychology, planar politics or societal disposition). In the ancient mind, the world was seen as flat and the cosmos extended above it, with each heavenly body moving in perfect circles above (an attempt to understand why the same star would occupy a different part of the sky at different times of the year). What if these cosmic rotations of the empyrean were the wheels of countless irreconcilable alignments and orders, each arrayed against each other and against the terrestial surface in complex webs of machinations, alliances and feuds. Only when the different forces arrayed against the urth had come into perfect balance, and these stars were in perfectly aligned, would true Neutrality reign and draw forth the old ones. At last, the stars are right.

Appendix A: Alternate Alignments

I find it is important to move alignments away from Platonic absolutes. In the Warhammer setting, the human psyche itself makes an impression on the metaphysical, and massed human emotions and thought can empower or even create entities in the raw chaos of the beyond. When you stare into the void, sometimes the void stares back. Here are d24 alternate alignments to drop into your campaign.

1 Psychological (from the village's deep-seated fears)

2 Chemical

3 Radiation (from the nearby nebula)

4 Planar

5 Linguistic (from the dead language recovered by the scribe)

6 Magnetic

7 Musical (from the mindless cacophony echoing in the deep)

8 Ethical

9 Elemental

10 Rhetorical (from an argument long forgotten)

11 Temporal (pouring forth from the black hole)

12 Cultural

13 Political (of the local petty barons)

14 Familial

15 Artistic (of the last masterpiece of the legendary painter)

16 Energy

17 Ancestral (from the forefathers that look down upon their tribesmen)

18 Philosophical

19 Moral

20 Gravitic

21 Mechanical

22 Mythic

23 Poetic

24 Organic (from the puddle of mossy slime by the roadside)

"The system of alignment in the DCC RPG is one that reflects its old-school heritage... Law is given as the choice of those who would uphold society's system of order and rules, producing the common good. Chaos is all about over-throwing authority, exercising personal power, and self-serving ends. The middle ground is Neutrality, the choice of those who choose not to decide, (hmmm...sounds like a famous Rush song of which I'm fond.)"

It is interesting that DCC specifically chooses not to equate Law with "good" and Chaos with "evil." Point in fact, the DCC RPG core book describes bugbears, goblins, hobgoblins, and troglodytes as being Lawful, and thus vulnerable to be Turned by chaotic Clerics. It is undoubtedly surprising to some that such traditionally evil creatures would be categorically Lawful in alignment, until you consider that there may be multiple axes that the struggles of the "urth" orbit around. Morality and Order are two such axes that do not necessarily always converge, as they have their own alien interests and objectives. Rather than seen as a graph or chart, perhaps aligning morality with order is better seen as a complex gyroscope, where good and evil is one ring and law and order are another (where even further alignments, include political, planar and magical could be included).

Certainly, neither pole of order (Law or Chaos) apparently comports itself to morality. As John describes:

"In my campaign, Law and Chaos will be struggling for dominance. Either potential outcome will not be good for the mortal folks of the world. If Law wins, the world become stagnant and unmoving. If Chaos wins, the world becomes a place of ever-changing pain and torment."

As the sun burns away and the old stars draw ever closer, ethics are increasingly merely short term sources of guidance. In truth, the dominion of either Law or Chaos will have an ultimately tyranical effect that will blot out all life. Law will crush its own people under heel, or simply allow them to die out and fade away in a perfect utopia, doomed by entropy like Tolkien's elves. Chaos will turn the world over into rioting and ruin. Neutral forces are aligned to the very passage of time itself, and seek either to prolong the titanic struggle that lays waste to the urth as long as possible before the imminent and inevitable end, or are entirely uninterested in the world's fate and worship the very fatality of it all. Dread Cthulhu, who would mindlesly tear the urth to pieces like a wet paper towel were he ever to turn over in his sleep, is notably Neutral in the DCC RPG book.

What I like here is that morality is something that veils the perhaps less obvious, but in the long term more dire, conflict. Morality concerns itself with the present, contingent and earthly situation, and represents an entirely different axis that intersects at times with Law and Chaos, which are more cosmic in origin. Ultimately, it is the ancient struggle between the latter forces, however, that march the world ever closer to inexorable collapse.

Here, the world is never to be saved, and the downfall is more or less inevitable. The urth is doomed, and stands in the shadows of a late age where the powers of order have long since committed to mutually assured destruction. This long tide from the deep oceans of the cosmos is drawing in upon the tiny urth, and will wash over its edifices and civilizations.

We can start to see a convergence between the concept of different planes of existence and the different interpretations of alignment (which has been, at times, a stand in for morality, psychology, planar politics or societal disposition). In the ancient mind, the world was seen as flat and the cosmos extended above it, with each heavenly body moving in perfect circles above (an attempt to understand why the same star would occupy a different part of the sky at different times of the year). What if these cosmic rotations of the empyrean were the wheels of countless irreconcilable alignments and orders, each arrayed against each other and against the terrestial surface in complex webs of machinations, alliances and feuds. Only when the different forces arrayed against the urth had come into perfect balance, and these stars were in perfectly aligned, would true Neutrality reign and draw forth the old ones. At last, the stars are right.

Appendix A: Alternate Alignments

I find it is important to move alignments away from Platonic absolutes. In the Warhammer setting, the human psyche itself makes an impression on the metaphysical, and massed human emotions and thought can empower or even create entities in the raw chaos of the beyond. When you stare into the void, sometimes the void stares back. Here are d24 alternate alignments to drop into your campaign.

1 Psychological (from the village's deep-seated fears)

2 Chemical

3 Radiation (from the nearby nebula)

4 Planar

5 Linguistic (from the dead language recovered by the scribe)

6 Magnetic

7 Musical (from the mindless cacophony echoing in the deep)

8 Ethical

9 Elemental

10 Rhetorical (from an argument long forgotten)

11 Temporal (pouring forth from the black hole)

12 Cultural

13 Political (of the local petty barons)

14 Familial

15 Artistic (of the last masterpiece of the legendary painter)

16 Energy

17 Ancestral (from the forefathers that look down upon their tribesmen)

18 Philosophical

19 Moral

20 Gravitic

21 Mechanical

22 Mythic

23 Poetic

24 Organic (from the puddle of mossy slime by the roadside)

Thursday, May 24, 2012

Review: Sailors of the Starless Sea

Sailors of the Starless Sea is the first adventure module available for purchase after the release of the Dungeon Crawl Classics Roleplaying Game. Starless Sea is meant to be an introductory adventure (for zero to 1st level characters), which showcases the different style of play promoted by DCC RPG.

The actual printed booklet is thin; only 18 pages, 13 of which comprise the actual text of the adventure (2 more pages are maps, 1 page of handouts, 1 page of full illustration and a 1 page flyer in the back for promoting the game). Noteably, only six of the thirteen pages of the adventure are full text, with the other two thirds of the book being rather lavishly illustrated in the moody style of Stefan Poag, Doug Kovacs, Jim Holloway and Russ Nicholson. This is good for inspiring the Judge and greatly adds to the art-value of the book, but a few of the pictures will be difficult to share with players as they share space with text.

The adventure itself is meant for 10-15 zero level characters, or a slightly smaller number of 1st level characters. For the uninitiatied, Dungeon Crawl Classics campaigns can optionally begin at zero level, where each player rolls up three to four poorly armed and equipped peasants. In a manner reminiscent of Warhammer Fantasy Roleplay, these would-be adventurers face a steep curve of natural selection, leaving only the strongest to advance on to first level after completing the first adventure. Although this method is optional, providing each player with multiple characters does a great job of achieving a number of things. First, it provides a learning curve for new players. Second, it allows you to get multiple chances to roll a great set of Ability Scores without compromising the "3d6 in order" mantra. Third, it adds a little bit of dark humour to the first game, which helps ease players into the campaign before there is a truly meaty plot for the players to sink their teeth into.

Without spoiling the story, the module launches the adventurers right into the action from the start. There is no detailed home base, and the adventure begins at the entrance of the dungeon with the presumption that the adventures will conquer it in a single expedition. Although there are parts that are indeed very deadly, there is a clever way to gain reinforcements during the crawl, and defeating the module in one go is certainly feasible for clever players. This last part is key, as there are monsters in the adventure that are almost certainly unbeatable and must be approached intelligently. There are enough clues on how to handle these "puzzle monsters," but overly brash parties will likely receive little more than a TPK for their trouble. These monsters are obvious and clearly horrifying enough, however, to not allow even the most jaded players to entertain the slightest hope of conventional victory.

The dungeon, an ancient Chaos Fortress, is detailed with intricate, three-dimensional maps that really come to life. Although there are relatively few rooms left in the crumbling pile, they are all varied enough to provide a really robust adventure. This seems to go directly against the OSR megadungeon mantra of "half of the rooms should be empty." Indeed, there is no grid of hallways and square chambers, and each encounter section of the fortress is its own mini-adventure, with excellent ambience, a unique story to tell and different challenges for the players. Its hard to esteem the maps enough, and Doug Kovacs has done an excellent job interplaying art and cartography to paint a vivid terrain in the reader's mind.

Like the encounter environs, each lurking monster is unique, with no recognizable enemies to be seen (I believe this may be one of Joseph Goodman's design goals with DCC RPG). The treasure is also novel and original, with no +1 short swords to be found. Each artefact comes with a history of who owned it previously and a description of what dangers lie in possessing such a powerful relic. Some treasure will be evident to the players, but inaccessible until they advance in power, meaning that the party may have to return to the fortress later on to secure these prizes (which is a nice touch, suggesting a "Return to the Starless Sea" session down the road).

The action in the module can only be described as high-octane. Unlike a normal low-level adventure where the players are stuck rescuing the local merchant from goblins, Starless Sea throws beginning adventurers into what feel like major events. Instead of relying on their ability (indeed, zero level characters have little), players must defeat high-level challenges with their wits (the puzzle monsters mentioned earlier being just one example of this). The end of the adventure leaves the players feeling that they have achieved larger than life things, although at a terrible cost, and creates an exciting opening for further adventure as the heroes are born away on perhaps the greatest prize and namesake of the module. There is also plenty of opportunites to draw long-term villains from the adventure, making the module a decent foundation for a larger plot.

For a dusty shelf price of $9.99 for the dead tree version ($6.99 for the PDF), and considering the amount of art in this module, it is hard to pass this by. The stats are generic enough to run the adventure with any OSR game, and (with a little editting for gore) Sailors of the Starless Sea would be an exciting introductory adventure for new players of any age. It is best used, however, to introduce players to DCC RPG, as (much like that tome) the contents are a very evocative old-school primer on how to bring that 1970's heavy metal ballad feel back to your gaming table.